TEXT KASHA LASSIEN @kashalassien

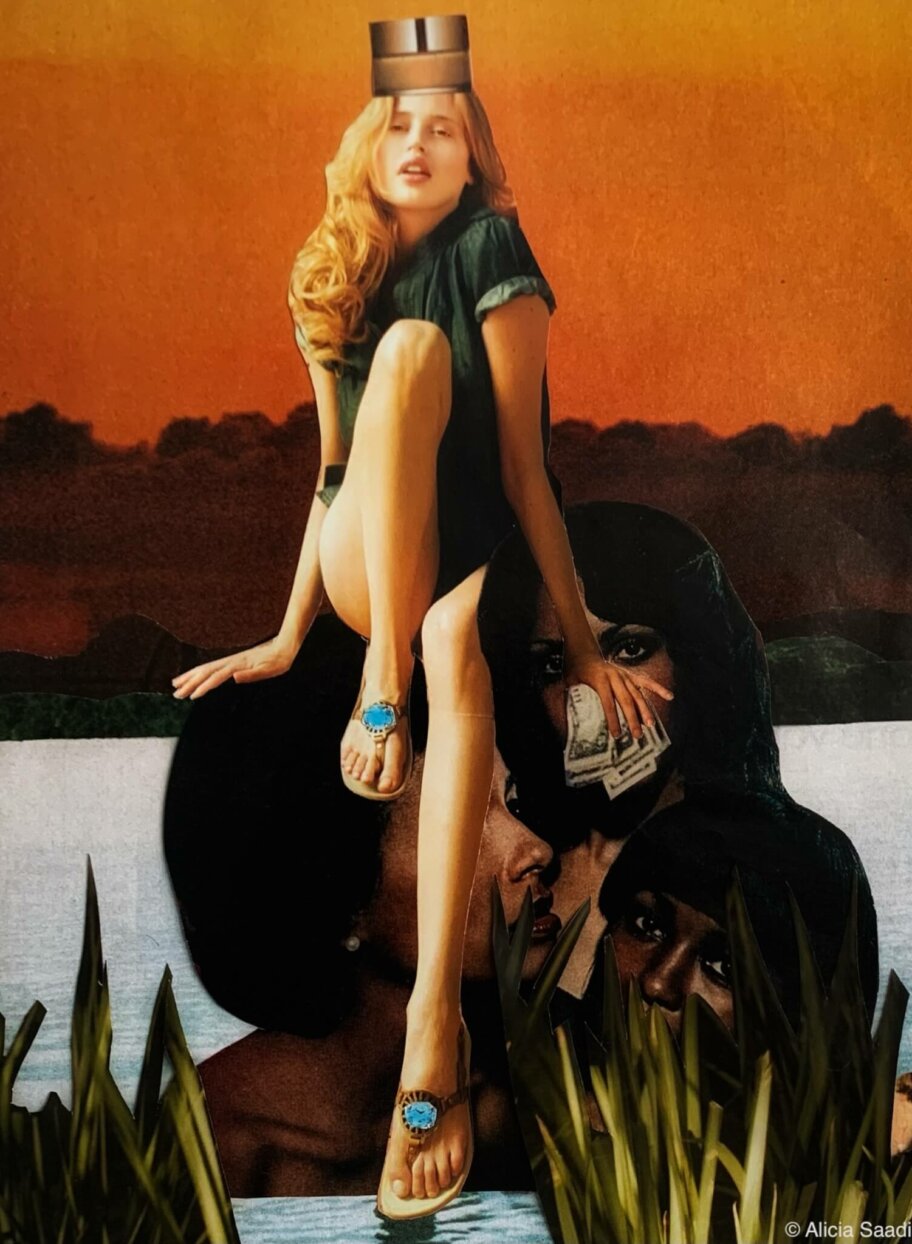

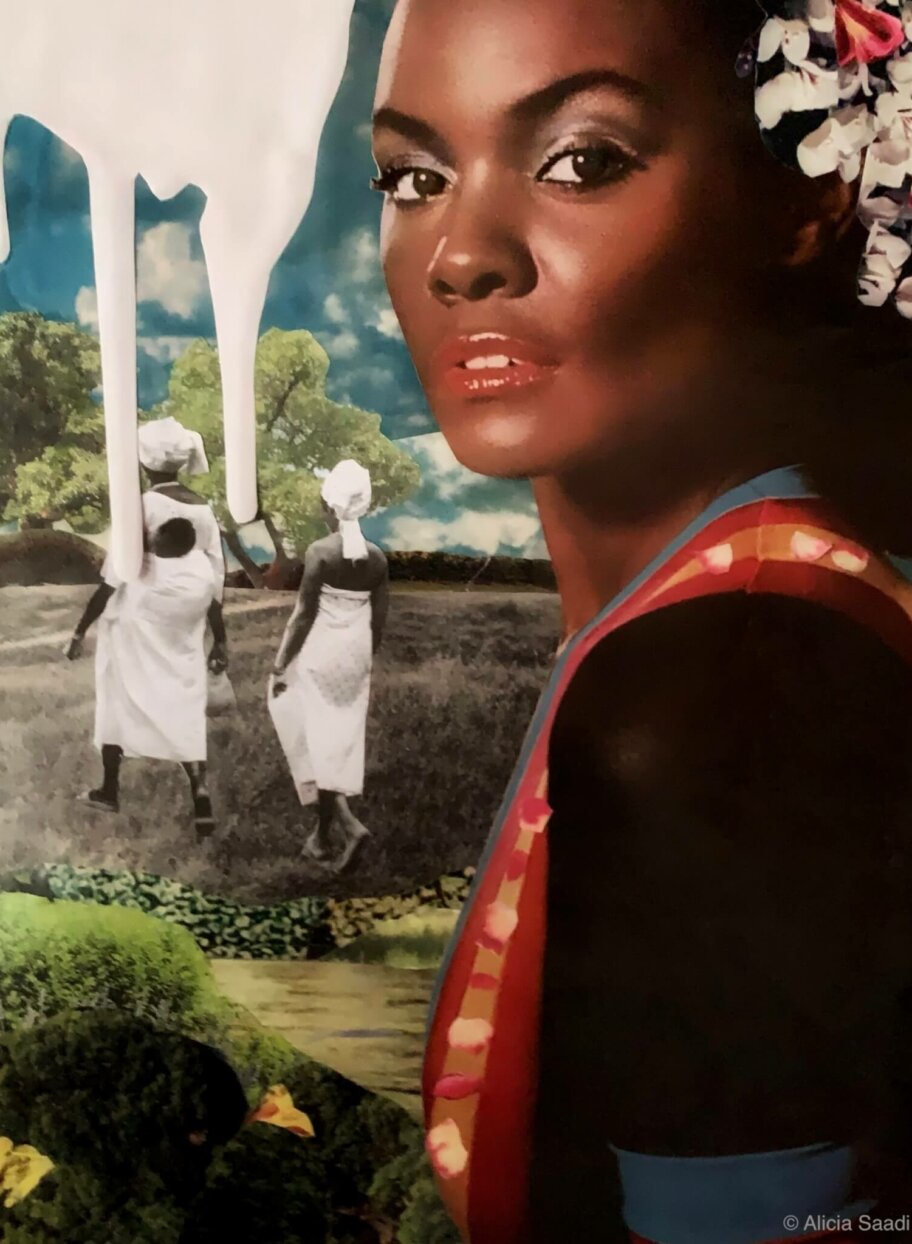

ARTWORK ALICIA SAADI @alicia_undomesticated

The dictionary defines Whitewashing as a form of cultural appropriation that portrays things in a way that increases the prominence, relevance, or impact of white people and minimizes or misrepresents that of nonwhite people. Sadly, we’ve seen whitewashing take place in the beauty and fashion industry more times than we can count.

Do you remember the Marc Jacobs Spring 2015 show? When the models marched down the runway in what was deemed “twisted mini buns” inspired by Bjork? It completely ignored the longstanding history and culture of the African tribes that have worn and denote this style as bantu knots. This was whitewashing.

Do you remember just last year when a white woman named Sarah Marantz scored herself a full feature in Fashion Magazine for creating the ‘NiteCap’, a “new” innovation that took the form of a silk bonnet to protect the hair while sleeping, as though black women have not been using bonnets for centuries to protect their hair from the drying materials of pillowcases? To top it all off, she charged, and still charges, upwards of $90.00 for one, even though you can find bonnets at your local beauty supply store for about $5 or less. This was whitewashing.

Sara Baartman, an African woman, was carted and objectified during 19th century Europe, forced to perform in freak shows due to her curvy body type. Now, a century later, the natural body type and features of black women have become “trendy”. Non-black women adopt bigger lips, smaller waists, and bigger buttocks which are, in some instances, cherished on non-blacks while rebuked on black women. This idea of accessorizing blackness while detaching themselves from our oppression is whitewashing.

Along with diversity and inclusivity, environmental sustainability also seems to be at the top of every company’s agenda as of late. The beauty industry has been implementing these calls to action in their approaches to beauty, but as a black woman, the colonization of BIPOC beauty aesthetics has always been apparent to me and I have not forgotten. Is this new frenzied race into “clean beauty” just another gentrified movement? Does whitewashing exist in this space, and if so, how are blacks and other minority business owners navigating through it? I caught up with Jazmin Alvarez, the owner of multi-brand clean beauty and wellness market place – Pretty Well Beauty – which curates the brands that are exceeding the industry’s standards of ‘clean and sustainable’ to gain a little insight.

Jazmin reminded me that “clean beauty” is just natural beauty that originated with people of color. “People of color have been using elements from Mother Earth since the beginning of time for all of our beauty and wellness treatments, healings, remedies, etc”. We find evidence of this when we study ancient African tribes and some of the world’s oldest groups of people. When we take a closer look at the continent, we see the use of natural ingredients in their everyday routines. For instance, African black soap, which can be extracted from the ash of plants, made from the skin of sweet potatoes, or taken from cocoa pods’ ash, has recently become a mainstream phenomena but has been used by Africans and those of the diaspora dating back hundreds, even thousands of years. With just a little digging through BIPOC history, African history specifically, you will find Neem Oil used for moisturizing and alleviating itchy skin, alum stone used as natural deodorizers, lemons for toning and brightening the skin, qasil for ridding wrinkles and dry scalp, and of course, the milk and honey baths used by none other than Cleopatra herself. When we turn our gaze to South America and look toward Peru, we see the use of maca powder, which contains a host of vitamins and minerals and has been said to help improve libido and alleviate menstrual cramps, spanning over 3,000 years. This thread of commonality continues forth across the globe with beauty regimens and secrets passed down from generation to generation as a part of BIPOC heritage.

When asking Jazmin about some of her personal “clean beauty” routines that have been passed down from her mother to her she said “We used food from our refrigerators and pantries, things like oatmeal, honey and bananas for our face masks. We weren’t really sure what we were doing, but we knew those ingredients had healing properties.” We both reminisced on the memories of sitting between the legs of our mothers while getting our hair treated for the week. “My mother would use eggs, olive oil and mayonnaise in my hair to keep it strong and shiny. She always told me to use things that were natural and taught me that using less was more.”

Jazmin continued to speak about the cultural ties and connections that are shared in BIPOC communities. “I think that’s very much a cultural thing across a lot of cultures, not just my family. It’s prevalent in black families, Asian families, Indian families…everybody, except for white families. The egg and olive oil mask, that’s something we all know about, but if you tell that to a white person they are oftentimes surprised because they didn’t grow up being exposed to that stuff. I don’t have any white friends who have ever told me that they have had experiences like that. It was always my friends, who were people of color, who were able to relate to me in this way. Clean beauty has always been around, it’s been around since the beginning of time, but some white person decided they had discovered the power of using plant-based skin care and decided to capitalize on it. This popularized clean beauty catapulting it into mainstream media. White people are the majority, and historically have the biggest and most influential voices, but we all know that everything that’s cool always originates with people of color and clean beauty is no exception.”

When we begin to look at “clean beauty” in the market place we find that –according to a forecast by Persistence Market Research—by 2024 its value is estimated to be $21bn and expected to continue increasing with majority of clean beauty brands owned and operated by white people. Yet in 2017, African Americans alone represented 86% of the ethnic beauty market making $54 million of the $63 million spent according to Nielsen. However, these products aren’t typically marketed to people of color leaving large amounts of shoppers ignored. It seems like we have been left out of our own stories.

I wanted to know what inspired Jazmin to get into the “clean beauty” space. She told me a story about a horrible shopping experience at a New York clean beauty store where she felt largely ignored and saw a lack of representation and diversity in the employees, brands on the shelves, and the marketing. She said that was what planted the seed for Pretty Well Beauty.

I couldn’t stop thinking of her story as I walked down the aisles of my local grocery stores, well aware that the death of George Floyd and the acceleration of the Black Lives Matter movement in June of 2020 had ushered in a slight change. We saw an increase in brands including more BIPOC on their social media and their advertising. These brands, who had little to no glimmer of color before, began utilizing BIPOC as their seasonal roll outs leaving many of us side eyeing and wondering if it was all just a performative act to placate our communities. “With the #PullUpforChange initiative, you are seeing retailers like Sephora and Credo take on more black and brown brands to sell in their stores, and it feels very strategic. If none of those things had happened, would they even be carrying these products? It’s so obvious that there is a lot of colonization still happening, but now it’s being disguised as “doing good.””

Behind the beauty industries performative initiatives that have been flooding our timelines, another sinister evil is, and has been, taking place. There are exploitative measures that happen in the creation of beauty while simultaneously gentrifying the natural beauty routines originally used by our ancestors that have been marketed as anything but historically BIPOC. This uglier side of the beauty industry is made up of so many exploitations of labor and illegal harvesting practices that are ravaging our Earth. In a lot of cases, we are witnessing ingredients popularly utilized by peoples in other minority cultures (be it African, Middle Eastern, Native, Indigenous, etc.), be illegally harvested, reappropriated, and then bottled up in our new anti-aging creams. These ingredients are co-opted and then sold for premium prices bankrolling the investors and owners of these “clean beauty” brands while simultaneously destroying the lands and habitats they are indigenous to. “If you are taking an ingredient and it’s not being harvested in a way that is going to preserve its life and function for the environment, it’s not sustainable. You are actually just stealing. You are taking and not leaving anything behind for the generations after to benefit from and use in whatever capacity they were meant for. Over harvesting is not a sustainable practice and it’s why I always say, not all clean beauty is created equally. Clean beauty to me doesn’t include any ingredients that have ever posed any potential threat to human health or to the health of the environment.”

There are some that are doing it right as Jazmin pointed out. MUN Skincare sources their ingredients in Morocco but works with local cooperatives from the Berber communities to pay the women real, fair wages for their work, wages they can actually afford to live off of. But, as you can imagine, this is seldom the case. An overwhelming majority of the time, locals who are indigenous to where the ingredients are grown, who possess the knowledge and skillset to properly harvest these ingredients, make little to no profit from the rituals and routines they have been accustomed to for ages. Still, we race to buy the new “it” product and perpetuate the cycle, all the while our wrinkle free foreheads serve as contradictions and tell the story of our opposition to the very nature of what is conscious consumerism.

The question is, who is to blame for this? I place the onus on those who are complicit in the whitewashing. I believe it is our responsibility as humans to step outside of our boxes to explore and learn things about each other’s cultures, beliefs, etc. I also blame media and the entertainment industry for its continuous efforts to eradicate blackness and other minority groups. In this aspect, media has been detrimental to BIPOC cultures. It appears that media has had an agenda of whitewashing. Of erasing and then highlighting the image of us they have deemed palatable. They have decided our cultures are something to be hip to, something to steal from, but not something that should be protected, appreciated and respected.

It is easy, and necessary, to hold consumers accountable. At the end of the day, we have been taught that our actions affect others since childhood, and it is our responsibility as humans to educate ourselves, explore, and learn things about each other’s cultures, beliefs, etc. It should not be this easy to misdirect us, but when the media we consume daily continually tries to eradicate blackness and other minority groups, there are more fingers to point. The media’s agenda has been one of whitewashing, and it has been carrying it out successfully. Something needs to change, and the beginnings of that are already being seen.

We must continue to challenge and make this agenda an uncomfortable one to carry out. We must call on our allies and have them hold their own people accountable. We must fire the beauty industry that is still complicit in cultural appropriation and whitewashing. We must continue to take up space in the game of ownership while investing back into our own communities. We must decide to support each other by intentionally patronizing BIPOC businesses, especially in the beauty space. We must arm ourselves with knowledge and unlearn this strand of conditioning that looks outside of ourselves for validation. We must support each other by sharing information to prevent another from experiencing the same pitfalls that we did. We must turn to our own forms of media and outlets, where we are the narrators of our own stories, to express ourselves. We must call out those who would stand to be vultures and colonize our culture for their own gain. If you are an active participant, there is an end in sight. If you think this isn’t important, or too big of a job, or are just too comfortable to push back, they will swallow us whole.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |